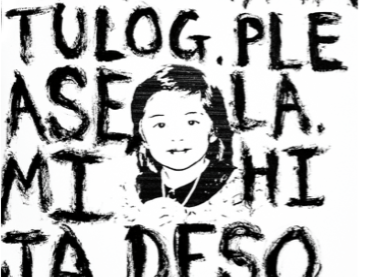

Malina Abella Salud, is a new body of work by Studio Artist Angela Hien Buencamino Phung. Wading through a deep well of re-adaptation, self-evaluation and healing, Phung has created a beautiful compilation of visual and written work, bound together into a book, and brought to life through movement and performance. Inspired by poet Ocean Vuong, she mines the perennial power of being and art making to heal inter-generational traumas and tend to her community. Phung investigates the beauty and pain associated with her mixed race identity via spoken word. Phung’s usage of evocative language and xeroxed archival familial photos traverse past, present and future histories, creating a sense of timelessness throughout every page and movement.

Chanell Stone (Exhibitions Fellow): Please tell me a bit about your background and your practice.

Angela Hien Buencamino Phung (Studio Artist): I am the daughter of Maria Lina, who was born in the Philippines, and Nam, who was born in Vietnam. My practices as an artist, community member, educator and learner are grounded in a persistent curiosity about the potential of a collective imagination.

CS: What is Malina Abella Salud? Can you explain how this body of work came to be and why you chose this form?

AP: As I processed the January 2020 Taal volcano eruption, I wrote a poem about the event from the perspective of a mother telling the story to her anak, her daughter. I experienced the disaster through news media, and Messenger chats with my loved ones in the Philippines. The TV footage of the eruption depicted softness that felt insidious, mirroring the distortions of knowing and remembering that are perpetuated by western media and Eurocentric historical narratives. It prompted me to meditate on what it is to bear witness to or live through disaster so impossibly large, like trying to grab ash. It is a reckoning with how we speak and hear about disaster and grief through generations, as well as a suggestion to hold each other closer in the process. The poem has since been woven with visual and written pieces, and manifested to a seventy page book in March. When revisiting the work recently after several months, I felt that sound, word, and movement were necessary dynamics to capture renewed connections within and surrounding the work.

CS: What led you to explore your familial histories and ancestry so intimately?

AP: The truths that want so badly to hide in the back of our throats, are the ones that hold the most pain in their silence. The mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual wellness of those who I share blood with, lay mercilessly at the intersection of sociopolitical and environmental disaster. When I write my name, start to finish, including the names of the ancestors that I know of through oral stories, I can trace with my finger the timeline of colonization and occupation of the Philippines. History is intimate. Familial and personal silences have been a survival tool…one that is exhausting. I hope to join with my own family in shifting this, and color in the complexities that lay within difficult narratives. It is at times a painful process. My intention in sharing this work is that it may inspire others to shift hurtful patterns into ones that support the health and potential to thrive for them and their loved ones.

CS: What does performance art mean to you and how do you use it to explore your artistic inquiries?

AP: I find it very scary to be visible. This fear is perhaps informed by aspects of my own neurodivergence. Performance provides me with a challenge in vulnerability, in a way that is genuine and hopefully meaningful. Specific to this piece, the movement of untangling felt natural to the process and content. As a child, I was able to self soothe through untangling and re tangling balls of yarn for hours, and by re inhabiting this motion, I gave myself permission to feel small in the deep well that this piece opens for me.

CS: I am enamored by your use of language. Can you explain your relationship to language in your practice?

AP: Language is a constant tension point for me. As someone who grew up in a home with multiple languages, while only being fully fluent in English, I find simultaneous empowerment and frustration, in the expanses that the English language can and cannot hold. With this body of work, I reflect deeply about what it means to re-cast a narrative that has impacted so many people. I feel deep concern about aestheticizing a fresh wound, in the English language that holds implications of imperialism in the Philippines. My fear is that this piece may perpetuate erasure through metaphor, of the very real impacts on folks in Batangas. As I continue to untangle wounds, meeting them with radical tenderness and honesty, I am able to hear the echoes in other narratives of the oppressed and understand with more clarity their points of intersection and diversion. Ultimately, I do believe there is value in naming, as a means to begin to grasp.

CS: You move between the past, present and future in this project. What does time mean to you and what does it mean to dedicate this work to a future ancestor not yet born?

AP: “You had not been born yet, anak, but you held me.” That’s how it feels. Istrive to listen, to and carry the presence of my ancestors as best I can. My own journey of being and healing has included re-parenting, and within this I have found affirmations, especially those with Tagalog inflections, can shake my core. The generational oscillations of the narration voice feel the most honest to me.

CS: Did covid-19 prompt this new body of work and if so how?

AP: I was working in education and food/art service early last Spring, and lost employment when quarantine hit. This forced me to slow down, and reckon with the ways that inter-generational trauma have rippled throughout my life. Simultaneously, I am confronting the white supremacist, capitalist and patriarchal systems that aim to cement those cycles, as I watch the pandemic unfold, disproportionately impacting poor black and brown women. I am dismayed at the empty resilience narratives pushed by mainstream media, or corporations motivated by greed, that further justify the exploitation of the oppressed. Angry. Confused. Disheartened, “tasked to build. build. build. still.” I found myself clinging to everything that I have learned from my teachers, peers, elders, loved ones, and favorite artists so dearly, and leaning on artistic expression to ground and guide me.

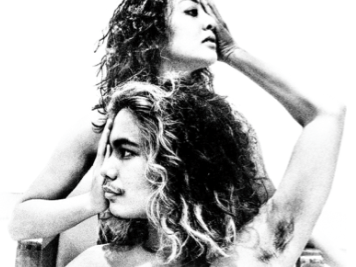

In particular, there are multiple people that deeply informed this body of work. Ocean Vuong, Theresa Cha, Maya Chan, bell hooks, James Baldwin, June Jordan, Maya Angelou, and Chavela Vargas, who’s art and writings are held very closely and dearly. Sydney Peterson, who has been an unwavering creative soundboard. Dan Sackheim, Rickie Cleere, and Aisha Gracie Moniz de Aragao Faria, who’s remarkable mutuality in love has helped me find strength on the worst days recently. Francesca Spriggs and Andrea Cajucom, my Pinay siblings who’s physical artistry is captured in some of the featured images. My blood family, who’s oral history contributions and Buencamino archival photos help me see myself and the world clearer. Chanell Stone, for curation, and documentation assistance. I feel very humbled to be, create and share. Ingat.

All Images :Malina Abella Salud, 2020, book (excerpt)

Angela Hien Buencamino Phung’s solo exhibition Malina Abella Salud is on view online in the Frank-Ratchye Studio Artist Project Space at Root Division from December 9th to December 22nd.