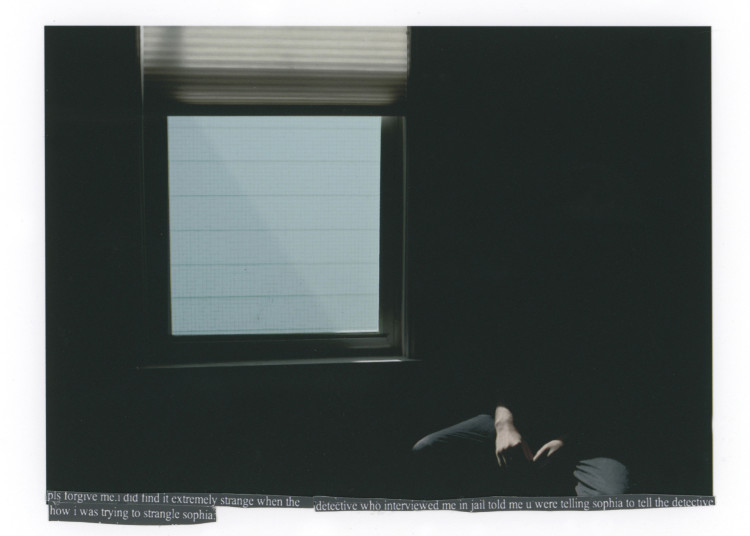

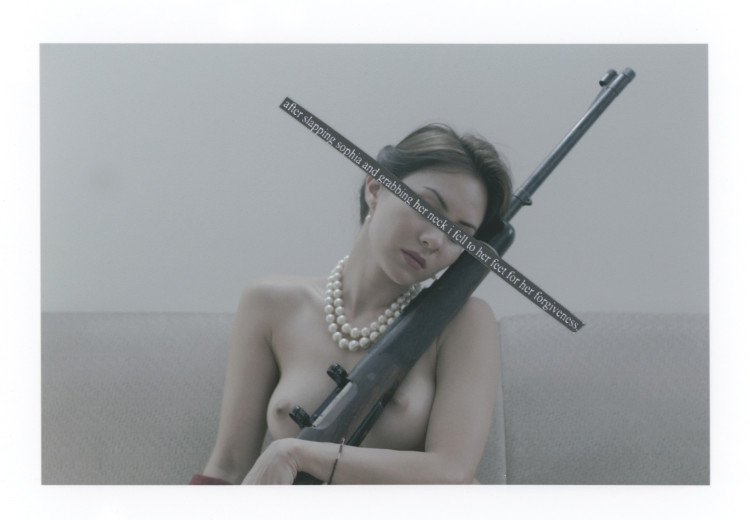

This month in the Frank Ratchye Project Space, we are excited to feature work by Studio Artist, Guta Galli. Her showcased photo series, Dear Guta, Please Forgive Me, exposes the struggles of confronting sexual assault and gender-based violence. The realities of facing such traumas brings forth an unapologetic style of vulnerability that has been a powerful force throughout much of her current projects.

Galli was kind enough to speak with Exhibitions Fellow, Renae Moua about the series, her shift towards performance art and multidisciplinary mediums, and the important connections she draws between art and identity politics.

Renae Moua (RM): In Dear Guta, Please Forgive Me your work features collage onto digital photographs that you had taken in 2010-2015. Why do you feel it was important to revisit these photos and build upon them years later?

Guta Galli (GG): It was very important to revisit and transform these photos in 2016, because they represent the moment of my feminist awakening. Unfortunately, my awakening happened only after I witnessed rape and domestic violence right in front of my eyes. That’s when I started really thinking about rape culture, and that’s when I started educating myself in relation to feminism. I was born and raised in a very sexist country, and I guess this culture was so ingrained in me that I was probably reproducing it with very little or no awareness.

RM: How was this project important for your growth as an artist and the projects that you have made currently?

GG: Being awake is far from enough to make a contribution in relation to repairing the damages of the patriarchal predatory culture, but it was a start for me. And these pictures – and the reactions that they provoked at SFAI – motivated me to go further in my research and expression, and led me to start performing.

In Dear Guta, Please Forgive Me, I was exposing the patriarchal male transnational fantasies projected on women’s bodies, and the violence that this gaze generates. In my series The Minotaur and Us I was investigating how this same violent patriarchal gaze affects women – either connecting or disconnecting them. And, finally, I was also investigating what we actually are beyond that gaze, and beyond the stereotypes that are associated with our gender, race, body shape or age.

RM: I’m fascinated by the number of disciplines that you work across from photography, video, installation, performance and so forth. You seem to do it all. Why choose to work across mediums? Do you have any mediums that you felt have been more challenging to work with than others and if so, why?

GG: I worked most of my life only with photography, but there was a point in my artistic research that I realized that I needed to use my body to address my conceptual interests in a deeper way. This happened right after I did my photographic series Dear Guta, Please Forgive Me. The theme of this work is rape culture. Since this theme involves body vulnerability, it made sense to me to abandon the comfort zone of my traditional medium and use my body instead.

The first performative experiences opened up the door for other mediums as well, like video and installation. Today, It’s clear to me that it’s important to keep working across mediums for two reasons: each idea demands a specific medium. The choice of the medium can’t be related to what you are familiar with. Besides, it’s important to keep changing them to keep the creative tension alive. Comfort is dangerous for artists!

RM: In many instances when women speak out about their experiences facing gender-based violence, they are met with backlash and silenced by dominant society. As someone who creates work that incorporates controversial ideas related to gender, sex and race, what has been your audience’s’ reaction for the most part? Have there ever been times when people have pushed-back on your work, and if so, how did you respond?

GG: Fortunately, I receive a lot of fantastic feedback. But it is not uncommon to receive negative reactions such as discomfort or embarrassment, shock or hyper sexualization of my pieces. The hyper sexualization comes mostly from heteronormative men, not surprisingly.

My work also tends to divide feminists. Many embrace my practice with a lot of respect and enthusiasm, but some just absolutely hate my work. When I have to face aggressive reactions, I try my best to patiently use that energy to create dialogue and enlarge perspective. If it’s not possible, I just observe and try to learn with them. They often inform and appear to confirm some of the ideas that motivated the work.

RM: In your performance brid(g)e you embody a “female figure dressed as a bride” and crawled for over 2 hours from Market St. to Root Division’s 15th Year Anniversary Celebration. What was your thought process behind this performance? What were your expectations, hopes, and/or fears going into this performance and what did you take away from it?

GG: For this piece, I was inspired by W. Pope L. I was referencing his phenomenal crawling pieces and talking about my reality in the US: being a female, brown immigrant artist in San Francisco in the Trump era. The bride was not a reference to love and marriage per se. It was about the marriage between the art world and immigration politics. It was a reference to the very dangerous and romantic idea of being an artist in San Francisco.

My expectations were to create a compelling piece that would impact myself deeply , as well as the audience in Root Division, in the street and online. I had the hope that people would see beyond the obvious reference to romantic love. I expected people to also see that it is a lot about the city of San Francisco today. My only fear was that I would possibly face physical violence in the street. It end up being probably the most profound spiritual and emotional experience I have ever endured. I felt more connected than ever to my practice. I experienced the pain, alienation, beauty, power and freedom of this city in an unique way that I really can’t translate into words. Yet. And I also experienced a deep, dark depression that lasted about a week. This existential emptiness was much harder to overcome than the crawling.

RM: Along with the important feminist issues that you shed light on through your performances such as brid(g)e, The Minotaur and Us, and the Cup of Tea series, you also seem to put your body through very excruciating situations. In your experience, how can performance also become an exploration of the limits and possibilities of the body? For instance, does performance reveal to you things about yourself, both on a personal and creative level, that you didn’t know before?

GG: Definitely, performance can totally become an exploration of the limits of the ‘bodymind’ (no separation!).

Since the first performance, I started using it as well as a very rich resource of self-knowledge. I have learnt many things about myself that I didn’t know before, on all levels. Some of The Minotaur and Us performances, for example, have triggered emotions or memories that I wasn’t aware that I was carrying with me. But I wouldn’t call it therapeutic. I would say it creates very rich material to be discussed in therapy.

RM: To conclude, how has your art practice changed over time? Can you elaborate on who or what has been influential to your art practice?

GG: My art practice changed immensely in the last 3 years, when I moved to SF to pursue my MFA at SFAI. This huge change provided the right environment to simultaneously concentrate and expand my artistic practice. In other words, I felt free to dive deep and wild into my practice! I needed a space that was very serious and widely open-minded for that to happen, what I could not find before.

The main transformations definitely have to do with 3 aspects of artmaking: using my body as a medium in most of my pieces, making my pieces more conceptual and interdisciplinary than ever before and making collaborative work: I used to feel isolated artwise in Brazil, and here I started to collaborate more than ever with other people. For my Minotaur and Us series, for example, I involved more than 30 women in my performances!

For more specific influences, I would say that, in terms of readings, what impacted my work more was Intersectional Feminism and Gender/ Identity Studies and Philosophy. The artists that have influenced me more were Ana Mendieta, A. Piper, Vito Acconci, William Pope L, and the authors were Peggy Phelan, Jane Blocker, Judith Butler, Julia Kristeva. And, finally, there’s one poet that recently started to influence me a lot: Solomon Rino. We feed each other’s practices deeply, and we started to collaborate too.