By Alicia McDaniel, Exhibitions Fellow

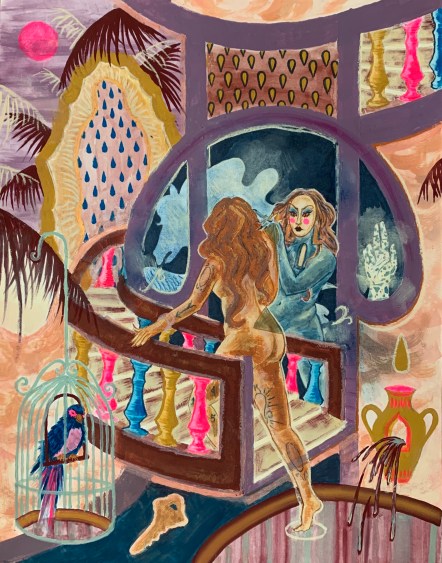

Alyssa Aviles is a visual artist and educator whose teaching and artmaking practices stem from her exploration of post-colonial identity. Aligning with her Latinx heritage the artist seeks to dismantle colonial oppression through her subversive, dynamic imagery of supernatural landscapes and figures. Aviles encourages her students to find meaning and liberation in creativity.

Read my full interview with Aviles about her background and the themes she employs in her work.

Alicia McDaniel (Exhibitions Fellow): Can you tell me a little bit about yourself and how you came to be a Latinx Teaching Artist Fellow?

Alyssa Aviles (Latinx Teaching Fellow): I was born and raised here in San Francisco, and I’ve always been really inclined to create. I have been drawing since I was a little girl and that was the only thing that I ever wanted to do. As I got older I went to a high school that was focused in the arts, and I was lucky to start my practice pretty early and to then continue in higher education. I work primarily in printmaking and graphic art. These mediums are really important because they are very intricately tied to my heritage and for the themes I work in. Printmaking is very ritualistic, and it happens in a lot of different ways, in different processes – you never know what you’re gonna get but then there’s this whole other aspect of it that’s very political and tied to social justice. It’s been a really powerful medium for me, because it addresses all the things I care about especially as a Latinx person. It’s a powerful tool to amplify our struggle and our voices, which is very important to my practice as an artist and a teacher.

I found the Root Division Fellowship actually through Francesca Mateo (RD Filipinx Teaching Artist Fellow.) We used to teach together at Youth Art Exchange, which is an organization where we teach high school youth. We had a social justice emphasis in our work, and Francesca was telling me about the community at Root Division, the structure of the fellowship, and how she was immersed with people within our own communities, heritage, and culture. It just seemed like a fitting thing for me.

AM: In your artist statement, you mention “spiritual geography” and “the divine feminine.” Can you elaborate on these terms and how they play into your work?

AA: I first came upon the term spiritual geography in undergrad. It’s about navigating through these borderlands that are physical, but also spiritual and psychological as well — being a person of Latin descent who is in America, out of their native land, feeling different pulls in regards to identity. Am I American or am I Mexican? Or am I this? There are so many layers in who you are – and this sense of you is not enough of one thing and not enough of the other thing – and this is the in-between state. Discovering spiritual geography was really a defining moment for me to articulate this sensation that I haven’t been able to elaborate on before. I think that is something a lot of people who are descendants of immigrants or who are immigrants themselves feel. This “in-between state” of being in one place or the other is something that I really relate to and what fuels my work.

As for the divine feminine, I think that in my work I am a feminist by nature and ever since I was little I only liked drawing women. At first I couldn’t really explain it, I didn’t know why but as I got older and explored my thoughts I realized that those images were evidence of this. There are so many injustices, stereotypes, and barriers that women have to break daily and I think that it’s really interesting to think that centuries and centuries ago women were worshipped and appreciated for who they are and their encompassing powers. Ever since I have been tapping into that I’ve been researching how power dynamics started forming and how Capitalism really influenced these gender norms and all of these political, social systems. I think that in everything I do I always go back to the divine feminine as I am trying to connect that ancient philosophy to where we are today. Which seems like something that is difficult to even imagine and something I always include in my work whether its obvious or more subdued. It is something I believe in and something that everyone should look into: just really try to pay attention to violence against women.

AM: Can you expand on how your work speaks to themes of displacement, assimilation, and the post-colonial identity?

AA: I think that all these are related. Indigenous cultures are associated with the earth, nature, just natural existences and the feminine, motherly. I think that earth itself is viewed as a feminine concept, it’s like our mother, and thinking about how this world’s resources are exploited is directly linked to the exploitation of women. It’s crazy to think about how all these concepts are intertwined, which is what I try to explore in my work. Post-colonial identity is really such a puzzle. I’ve been reading a lot within that vein lately and observing how patterns, behavior, and social conditions stem from a really violent past. Especially in gendered relationships – thinking about my family, other families, and people I know who struggle in poverty or domestic abuse.

AM: Can you speak to how these elements play into fostering creativity within the classroom?

AA: There’s a whole onset of imposter syndrome where you don’t feel that you belong in this place or you’re not good enough to be in this place. I think that this all stems from heritage, how you’ve been brought up, what you’ve been brought up to believe. Something that is deeply embedded in families is mindlessly passed on, something we don’t really think about. When these conversations come up with family, it is all unheard of and people aren’t usually receptive to it. But I think that the beginning of healing is to acknowledge these thoughts.

I think that as an artist coming from a Latinx family that’s a big statement in itself. I feel that our families and our youth aren’t encouraged to participate in art because we are in a mode of survival all the time. We have to make money, we have to be better, we have to be at a certain place, and “art doesn’t make you money.” I can’t even tell you how much of my life I spent hearing those words – even to this day. I think that it is really courageous for people to engage in creativity even if it won’t turn into a career. It is great in general to be creative and really let yourself feel. I feel that a lot of our folks don’t let us do that enough.