De’Ana Brownfield is a multidisciplinary artist and educator that currently resides in Oakland, California. She utilizes textiles, mural making, and painting to inquire about Afro-Indigenous traditional ways of being and visualizing Black futures grounded in healing. She holds a B.A. degree from Mills College.

Brownfield is currently Root Division’s inaugural Bay Area Black Artist Studio Fellow. This fellowship providesfree studio workspace and a monetary stipend to an emerging artist in exchange for being an integral part of Root Division’s Studios Program. In large part, the commitment involves a service project that aligns and enhances Root Division’s mission to empower artists, foster community service, inspire youth, and enrich the Bay Area through engagement in the visual arts.

Brownfield’s work is currently on view in the main gallery alongside her students as a part of New Growth 2021: Courage in Creativity, the annual Youth Art Exhibition featuring student artwork created in Root Division’s free after-school Youth Education Program.

Read more below to see Education Fellow Rebecca Sexton’s interview with De’Ana Brownfield about her experience as the Bay Area Black Artist Studio Fellow, as well as her own artistic practice.

Rebecca Sexton(Education Fellow): How would you describe your work and practice? What choices do you make, and why are they important to you?

De’Ana Brownfield(Teaching Fellow): My practice is very eccentric because I’m very eccentric. I like to dabble in a lot of different things, but something that I realized recently is that I’ve been really trying to work on decolonizing my practice, which means connecting more with traditional crafts, such as natural dyeing and weaving. At the beginning of this fellowship, I started off with just painting, but, later on, as I got further, I started working more with natural dyes like turmeric and indigo. I am trying to explore my relationship with materials that are connected with the African diaspora, as well as Indigenous people.

RS: Storytelling seems to be a foundational aspect of your practice. What does storytelling mean to you? How do you think about the materiality of stories and sanctity? How do you see the similarities and differences in your textile practice and your painting practice?

DB: I start with myself. As an African person, as a Black person, and an Afro-Indigenous person, our stories aren’t told in the way that we want to, and so, for me, it’s always this place of reconnecting with familiar things like food and clothes and style, all these different elements. I use that in a way to try to grapple with my experience and what it means to be reclaiming being African and being Indigenous. I started off with just that, and it kind of leads me into different things.

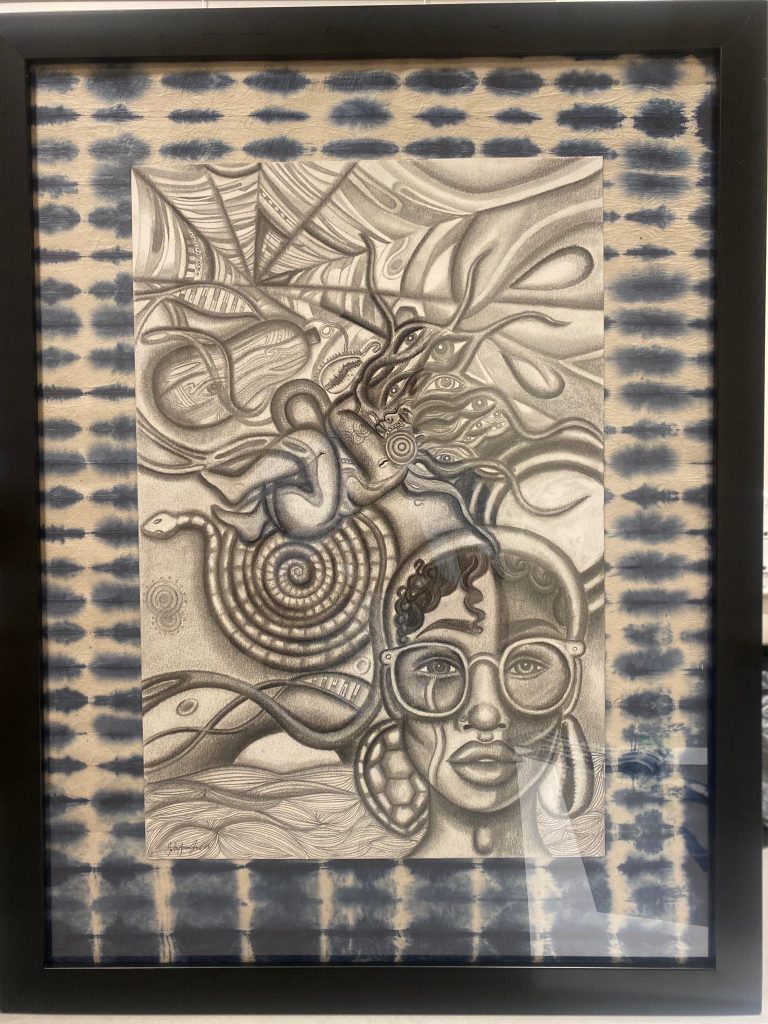

My drawings always have been self-portraits because I’m trying to figure things out for myself, and explore how I’m feeling and my relationship with my body and with the land. You know, living in this society where there’s a lot of issues with anti-Blackness, I just really try to use stories, specifically my family stories—how they were raised and the traditions we carry and things that we don’t practice anymore because of colonization. I am trying to really unpack it all. I do it in very different ways.

Sometimes, I’m called to paint. Sometimes, I’m called to draw or even start working with certain materials. Cotton has a really big impact on African descendants, especially that come from enslaved ancestors. So, I think about that history of how certain economies like the cotton industry, and the indigo economy as well, have been a big part in creating America, but also a lot of places were relying on those materials before those economies existed. I’m even talking about what those materials looked like before colonization because they were very important and Africa, and specifically in Nigeria. Indigo and cotton hold huge importance.

There’s always this balance of trying to tell the story of what has happened to African descendants, in colonization and slavery, but also talking about the history beforehand. Oftentimes, as an African person, we don’t always hear about the legacies that our people have had, especially as craftspeople and artists. We don’t get to explore that big history that people erase in the art world.

RS: How do you choose to engage in a particular medium to tell a story or to communicate a particular idea?

DB: It’s intuitive. I recently found out what indigo represents to West African people and that’s something I’ve been really drawn to for the past four months. I feel like my ancestry always tells me and directs me to certain mediums. I have Nigerian ancestry, so I have really been trying to learn more about that practice, and connect with as much as I can. That’s just the way it is. Sometimes I could just be drawn to something else.

It also has to do with the capacity that I have to make. It’s a mixture of both what can I do and what do I feel like doing. I don’t always have the capacity to do a whole bunch of thinking. It can be very complicated for me; sometimes because there’s a lot of planning, but working with indigo and other natural dyes is easier and more relaxed and freeing.

Also, it boils down to resources and space, so I feel called to go home to do those projects and also being able to have help from my family. When it comes to drawing, it’s always a time to reflect. When I’m overwhelmed, I like to do portraits. It’s a space of intimacy for me. I just do things based on how I feel. I try to do stuff that’s more personal rather than creating art based off of a specific location or concept. I know that’s terrible but, for me, I feel like it’s easier to work when I’m at home and I don’t have any other obligations. I’m on my own time, and I get to create.

RS: Can you describe the work that you have done this past year as Root Division’s Bay Area Black Artist Fellow?

DB: It’s been very nice. In the beginning, I was really, really excited about the fellowship and did a lot of projects around collage and using paper as a form of making quilts. I enjoyed that process, but with the pandemic, it makes for a very different experience. I didn’t really necessarily teach at a school. I felt comfortable teaching at and with organizations, so I partnered with AfroPlay and the Black Cultural Zone, and I did these different types of projects so started off with paper quilts, then moved into natural dyes with turmeric and hibiscus. We even did a tie dye activity, which was cool and a little challenging. It’s been a learning experience for me to work and share my art practice. Sometimes, I feel like I’m overly simplifying things. I feel like this fellowship has taught me a lot about myself, my process, and the things that I need to do better with.

The collage activity was my favorite thing. It was a specific project where I thought about the Gee’s Bend Collective in Alabama. It is a cooperative of black women who got together and created quilts to provide more income for their families. Their work is beautiful, and it’s shown in a whole bunch of galleries in New York. I thought it was really cool to get inspired by their work, but also include my own narrative about my Afro-Indigenous history. As a group, we explored things like mythology creation stories. It was really cool to piece those things together in paper, but still have the element of a quilt. My quilt had all these different things, and it kind of made me feel like I was in touch with my inner child. The kids’ quilts were based off of red, black, and green, and it was Black History Month. Red represents the blood—the blood that our ancestors shed on this land and, also the genocide, even though people don’t classify it that way. Slavery meant the enslavement of African people and genocide. Green represents the land. Black represents the people. I was trying to have them re-create the story of their family and history.

I wish I did more collage making and had more time to sit down with kids and work with them in the process of making collages while looking at different quilting traditions. There’s always another time to do that, but other than that I’ve been really enjoying the fellowship, connecting with my community, and learning about more organizations who are doing similar work.

I’ve always wanted to have a practice that my community can be involved in and the fellowship made me realize that I can be doing more hands-on projects with youth and teaching more about craft. This experience is also making me want to learn more about certain things like getting my sewing skills together, so I can teach people how to do these things. This fellowship made me realize the importance of trying to build up my skill set, so I can teach people how to do certain things like natural dye, because all those different things could be a form of income to sustain communities and families.

RS: Finally, can you talk a little bit about the piece of work you’ve chosen to display alongside your students’ work? How do you see your piece speaking with and to the work of your students?

DB: I was thinking about showing the paper quilts. At first, I was gonna put together this quilt, and sew it all together. I have kept working on making the little paper quilts, and I am also thinking about showing pictures of us with their work and have that part of the show because I thought that was really cool and that’s my highlight of the fellowship is like doing the paper quilts.

The kids paper quilts are connected, but mine is more of my own exploration of my cultural identities. Their quilts celebrate Black History Month and focus on the use of red, black, and green, which is slightly different than my own quilt. However, even the symbolism of red, black, and green connects. They all revolve around uplifting Black people in our stories with the land and the history, so I think they’re going to be well put together.

We have to recognize our history in order to move forward into the future; we have to look back to the past, so you know Sankofa represents those things. Those elements connect with my piece of work and their pieces of work, so you know I think it’s important to share that narrative and that way, whereas a lot of people see it as something of the past, but it still impacts, you know Black and African people globally. It’s important to have that level of awareness of how this is still a pressing issue.