Former Root Division Studio Artists Julia Sackett and Tom Loughlin discuss Tom’s work in anticipation of his solo exhibition “This Space Intentionally Left Blank,” opening at the Spare Change Artist Space this Thursday, February 19th.

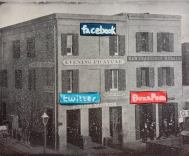

It seems appropriate that two artists working with manipulating the urban landscape are in conversation, even if one landscape is historically based, and the other one happening in real time. Julia Sackett’s recent body of work, which draws parallels between San Francisco’s gold rush and current tech boom, was featured at Spare Change last summer and was recently on display at The Old Mint.

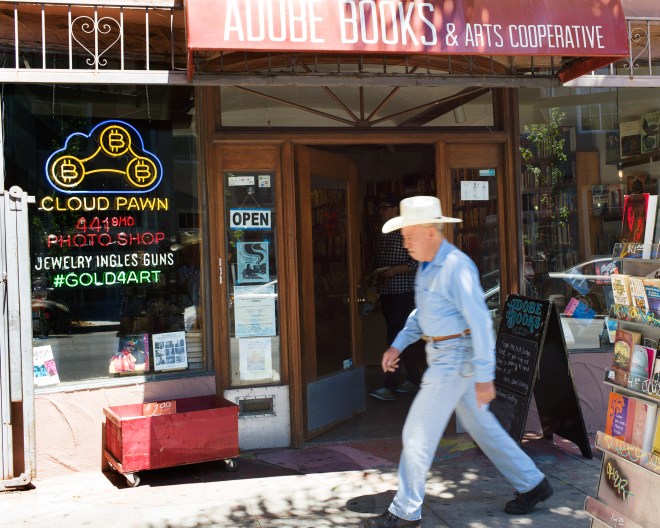

Tom Loughlin’s neon signs have been displayed in windows and offices all over the Bay Area ranging from the biggest tech company headquarters to the windows of small independent booksellers. Three of the signs were featured over the past five months in pop-up installations in the front window of Root Division’s Market Street location. In our heavily trafficked corridor between 6th & 7th Streets, the signs garnered a lot of attention–often eliciting confused reactions from passers by who believed Root Division was either a pawn shop, a strip club, or a check cashing establishment depending on which sign was glowing in our window. There were also moments of complete engagement–passers by reading the artist’s statement, taking a photo, staring inquisitively at the text, trying to decipher meaning.

In playfully re-imagining contemporary and historical signifiers, both of these artists are in the business of disrupting static boundaries of art and life–then and now–accessibility and exclusivity–commerce and community–and in doing so challenge viewers to consider their engagement and participation in particular Bay Area moment. It’s my pleasure to have worked with Tom and Julia on exhibitions at Spare Change, and to share with you this dialogue between the artists.

– Amy Cancelmo, Exhibitions & Events Director, Root Division

Julia Sackett: Tom, when I look at your work, I think about how many words the public encounters in a day. Words that try to coerce, sell, inform, entice. It’s so easy to ignore the deluge, but your work confuses the narrative. What is your relationship between blending in to the background and emerging from it? Are you trying to be sneaky? How loud do you have to be to disrupt?

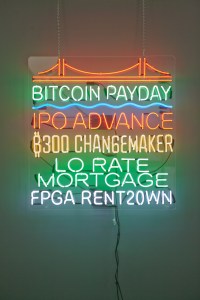

Tom Loughlin: With a lot of my work, I’m trying to make something that sits at a 15 degree angle from reality. It’s close enough to the everyday that it’s recognizable, but it points off in a slightly different direction. I think the idea that some of my art is sneaky comes from seeing the point of access as a kind of camouflage. That’s not a neon sign – it’s a subversive trap! I understand that reading of it, but my aim is to ask questions that I don’t actually know the answers to, whereas I think most modes of public address purport to know what’s best. If I know one thing about myself, it’s that I’m an unreliable narrator. I try to build that understanding into my work, and I’d definitely encourage you to think of me that way.

JS: Sometimes when I walk around the city, it seems too weird and wonderful to be real, like only someone planning these sights and circumstances could be responsible for such a poetic and weirdo reality. I get the same sense when I look at your work. The neon sign work seems like a poem to the real life divine. How do you make these things? Are the words you use pieces of things you observe, or are they made up entirely by you?

TL: I really hope I’m writing poetry to the real life divine! For the most part, the visual and verbal vocabularies are drawn from what I see around me. Sometimes they need a little turn, but sometimes they’re weird and poetic enough all by themselves. For example, that typesetting placeholder pseudo-Latin that begins “Lorem ipsum” has its origins in a Cicero treatise examining whether hedonism is a sensible method for enduring the human condition. In the original text, the words “dolorem ipsum” refer to the senseless pain in life that we all sometimes feel. Now it lives on as a ubiquitous nonsense phrase. That’s pretty weird, right? And the text is really a gift if you’re trying to link the ordinary and the transcendent. So those words found their way into a sign unedited.

JS: Just in general, how do you navigate making experiential artwork in a gallery? Can you make experiential artwork when it is not labeled or experienced as art? Is art still art when no one is watching? (ugh that question….)

TL: Ah, that question… People keep telling me that I make work that gets completed by the viewer, so I suppose that might be true. I know I’m interested in the way folks relate to the things I make, and I’m both delighted and disappointed that I mostly don’t know a lot about how the work is being received. At least with neon signs hanging in public places, I can see people taking a moment out of their day and engaging with the pieces, and I love hearing stories from people at the venues that host the signs about some of the ways viewers have responded. Apparently we’re confusing people across San Francisco.

Galleries don’t feel like the best venues for some of my work, mainly because the gallery goers have come seeking out an art experience. That encounter can be pretty abstracted from everyday reality, and I feel like most people don’t jump through the series of hoops that you need to pass through to arrive there. So it’s a particular kind of audience, and if you label something as art and hang it on the wall in a white cube, the viewers tend to relate to it in certain predicable ways. I’m deeply thankful that those venues exist and that people show up to engage with art in them – they’re just not always the best place for every project.

JS: Sort of related: what the hell is a Bitcoin, and who decides the value of worth anyway? I was just at the Old Mint deinstalling a show, and I was thinking about the first years of San Francisco, when there was no unified currency in the city (or even in the “continental” United States, but it was more obvious in the wild west.) Everything from nuggets of gold to Pesos to Pounds to personal objects was used for currency. There were three main privatized Mints in the city, each with a different gold standard. Is worth just something everyone agrees to believe in, like Santa?

TL: Like most things we’ve made, Bitcoins have whatever value we agree that they have. One nice thing about Bitcoins and most financial instruments is that there are marketplaces continually creating international consensus on the price of those items. So you can go online and, in a certain way, see exactly what Bitcoin means at any given moment – which makes it lot more concrete than other tools we use regularly, like the words “love” or “democracy.” We really rely on these things that we’ve created, like dollars and words and governments. We agree that they have value, and they facilitate collaboration, but they also have an inherent indeterminacy. I find that really interesting.

JS: What is your process like? Where do you do your thinking? Do you write, take pictures, record? What is the experience of being an artist like for you?

TL: The core of my practice is ideas more than materials, so that’s what I spend most of my time working with. And I feel like I’m working all the time, even though it might not always look that way. I practiced law for a number of years, and because of the way lawyers bill for their time, every six minutes I had to ask myself whether I was doing something productive. I guess that habit stuck with me, so it’s strange and wonderful now to be able to just be my curious, neurotic self and do the things that interest me and feel like it’s all productive work.