About six months ago, Michelle Mansour (Executive Director of Root Division) and I, were called into the offices of Rhodes & Fletcher, a financial planning office in downtown San Francisco for a meeting about curating their space. After that first meeting it became clear that curating, what they had dubbed the “Spare Change Artist Space,” would be a unique opportunity in an alternative venue.

The first exhibition that I curated in the space Downtown: Work by John Mark Ikeda, is currently on view through February 28th, 2013.

I sat down with Sean Fletcher, of Rhodes & Fletcher to discuss the impetus of this project and later with John Mark Ikeda to discuss his practice and thoughts about this current exhibition.

Amy Cancelmo in Conversation with Sean Fletcher

AC: Can you talk in your own words about how you came to be in this position in the first place? I think that your background is really interesting and was one of the things that made me think that this was an different type of space to curate. After that first meeting when Michelle (Mansour) and I came in here, I felt that you wanted to do something really artistically and curatorially interesting, and unique from a business model perspective.

SF: So I did my graduate work at the San Francisco Art Institute and at the time I was very interested in the economy in the United States and the fact that we didn’t appear to be manufacturing anything worthwhile for the rest of the world. In the process of exploring that, I tried to do something with my wife called Project Economy and did all kinds of little things, but in that process of exploring it I had this epiphany that we’re exporting a major good to the rest of the world, which is our sales savvy––it’s our technique at moving product around. So as a graduate student I figured that if I was going to write a thesis about this, I should learn to walk the walk and so I took a job at a life insurance agency with the idea that I would become an insurance salesman as a work of art. Which I did, I did that for about seven years. And while I was doing that I did crazy things. I tried to sell a life insurance policy to the SFMOMA on myself saying that I would really be worth something after I was dead. And I ran an art gallery out of my office. But that experience in life insurance sales was actually my entrée into financial planning. So when I finally did leave that position, going into financial planning was sort of a natural fit. I had accumulated enough experience there that I felt I could do something with it.

AC: So you still think of it as a work of art?

SF: No.

AC: It’s just a…

SF: No you’re going to say it’s just a job, but it’s not really just a job either. I mean, you come out of that environment into this environment. It’s a completely different thing. We’re helping people, and it’s rewarding and I don’t feel like I’m talking someone into doing something they don’t want to do. Which is entirely what I felt like when I was an insurance salesman. And I was not very good at it. This is problem solving. I think of it in terms of social sculpture as art, but I’m not out there documenting what I’m doing as an art piece like I was before.

AC: So then you become a financial planner. You have this beautiful office downtown across from the Wells Fargo headquarters with hardwood floors and comfortable chairs.

SF: Glad that what I’m delivering is a warm and comfortable environment to sit and talk in.

AC: It is comfortable. And, coming from the Mission District, it’s also pretty fancy. This building in and of itself…

SF: I think it was built in the 1880’s. It was the only building in the financial district that survived the 1906 quake. I think I told you that we had to sublet to a leasing agent, and they had photos that were taken from this building after the 1906 quake that were taken from this office. They were amazing because from every angle everything was just leveled. You had to be pretty high up to get a shot like that. Pretty incredible.

AC: Isn’t the marble all original? And those elevators are pretty incredible. It’s a very cool space that kind of speaks to the history of capitalism and America or the financial industry in San Francisco.

SF: Sure. It’s the Merchant Exchange building. So what happened is when the ship came in at the pier, the items would get traded outside but this was the spot where people came to do their trading and up on telegraph hill they had a good view of what was coming through the Golden Gate and they could say “we’re going to telegraph down to the Merchant’s Exchange that the silk boat is on it’s way and you’re going to start taking orders for silk, starting now.” So, that’s where we are.

AC: I think that history adds a curatorial interest for me. I’m interested in showing work here that relates directly to the space it’s being shown in and raises new questions. That’s not to say I’m interested in only showing work that is directly subverting or criticizing the financial paradigm in the U.S. For me it’s more interesting to find artists who can can poke at the foundation of the financial world in a certain way or maybe make things more clear––in the way that good art should do. That showing it here sheds new light on the entire experience, for you, for the people that come here, and for the artist as well.

SF: I agree that a good piece of art is going to leave enough doubt about the opinion of the artist that you have to think about it after you leave the work. That’s the mark of a great piece of art. If I sit down and look at a piece and think “this is really just criticizing capitalism,” and I don’t’ have a problem with criticizing capitalism, I encourage it, but to leave the piece and think, “I know exactly where the artist is coming from,” even if we’re sitting on the same side of the table, it’s a piece I don’t have to think about anymore. It sort of discounts the work. More than looking for artwork that pokes at commerce or the US economy or capitalism, what entices me are artists that are raising questions, like John-Mark, about the viability of it.

When we got this office downtown, I thought, it’s prime real estate and we could be exhibiting art here it doesn’t have to be placid decorative art it could be edgy avant-garde art. So that’s what I wanted. We were told that the best way to handle this from a regulators perspective so that nobody thought “what are you guys trying to finagle there in your financial planning office, that you’re really an art dealer” or something like that is to just have it be a separate entity. So we branded it a year ago and started calling it Spare Change Artist Space. We’ve only had about 2 exhibitions under that title.

I just didn’t know, I never felt we had a lot to offer an artist who wanted to have a show. I don’t have the proper lighting, I don’t have the proper walls, I don’t have what a traditional artist would look for in an exhibition space. In fact I don’t really have a lot of foot traffic.

AC: But you do have clients in the space. I’m interested to hear who your clientele are, if they’re interacting with the work, and if they are, if you’re talking to them about it. What has their response has been?

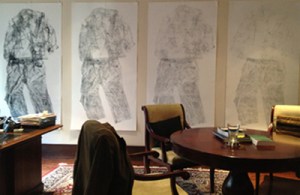

SF: Who’s coming in here? We do have minimums. So I guess you could say there’s a level of net worth that comes in as a client that is of a certain net worth. I tend not to stick to an investment minimum. I’m more interested in someone’s ability to save and manage their cash flow. And their ability to grow as a client as much as I am about what they’re going to put in our assets. When they come in, we always give them a tour. We’re pointing out that the prints were made from the suit on the floor, that they’re referencing quarterly figures, which is less clear as you go across. (Pressed and Q1–4) We can’t show them the Hummer piece. (Crash Test) We show them the poem. We take them on a little tour.

AC: I imagine your clients are excited to work with you because of this other project. It enriches their experience here.

SF: I think that if somebody didn’t come for this reason, after they’ve been a client for a while, there is a – is it a feeling of relief? Like ok, I’m not in the Merrill Lynch guy’s office. I’m not doing this same thing that every other planner that I’ve talked to is doing. I think that’s important to people. I think the presumption that people just aren’t tuned into contemporary art is actually false. I’ve learned that over the years of doing this in my cubicle or showing exhibitions here. People are very interested and when you get past the level of explanation like John-Mark likes to take things apart, that’s how he works. They’re like “Oh, oh,” now all of a sudden I get it even if I don’t know anything about art. I’m through the looking glass. It’s a nice place for people to be in. They don’t feel like an outsider, they don’t feel like someone’s poking fun at them.

AC: You tour them, you kind of give them the language; an access point to the artist, the work, and what you’re trying to do with the space. That’s exciting.

SF: Yeah, I think so too. Not all of our clients are going to go to the MOMA or Yerba Buena. Some of them are. Maybe 30-40% that are interested and engaged with art on some level.

AC: For us at Root Division, we’re in the interest of creating visibility for emerging artists that aren’t going to be at those places either. (John-Mark maybe being the exception because he did just show at YBCA). I imagine that most of your clientele won’t be at a Second Saturday opening at Root Division––maybe––hopefully they will, but either way it’s engaging them in the dialogue with what’s happening in non-profit, alternative spaces in the Mission or Oakland and making that accessible as well. I think it does often seem like distinctly two different worlds and it doesn’t necessarily have to be.

SF: When someone’s a non-artist and not accustomed to looking at contemporary work, the first response is ‘I don’t understand that.’ It’s the first critique. And then, you get to ‘I could do that.’ That’s the second most popular critique. But I think it’s the first one, you can pretty easily get past that. Just giving somebody a little access. Giving someone a little access changes their whole paradigm.

Amy Cancelmo in Conversation with John–Mark Ikeda

AC: When I was approached to curate this space, your work immediately came to mind because of its direct reference to the economy, the financial bailout, and the objects of professionalism. Do you want to talk a little bit about your practice to get started?

JMI: I spend a lot of time planning and thinking about upcoming pieces, or doing research. The initial ideas often come naturally, stemming from other pieces or perhaps a concept that I find interesting. It takes me a long time to develop each idea into a finished piece though. I create diagrams and consider different variations. At the end I’m usually working to reduce the pieces so that they can be direct, and that part often is the most difficult. I don’t think that they are simple, but it’s easy to try and over-complicate them. I’m very excited about some of my new video and projection pieces. It’s a new medium for me, so everything is little uncertain, but I’m interested in where it will take me.

AC: You reference the economy a lot in your work. Do you have any direct experience working in the financial world?

JMI: I don’t have any. I have friends that work in finance, but the pieces aren’t meant to only make sense to bankers. If anything the state of the economy has been in the popular consciousness for years now. Fluctuations in numbers frighten everyone, and often it’s unclear what impact they will have on our daily lives. I’m more interested in finance because it represents a rupture in our consciousness. It is something that we believe strongly in, but it has failed us and for a long time we have been trying to figure out why. At the same time, we have been working tirelessly to return it back to the way it was, sometimes at the expense of fixing the weaknesses in it. I don’t work at a bank, but every jobs report is a moment of anxiety for me. When the stock market fluctuates, I certainly pay attention. There is a constant fear that the economy will fail us again, that we will have double dip recession. In many ways, I wish it would return to the way it was, before I had to worry about it all the time.

AC: Curatorially this space is really exciting to me because of the implied audience and the direct contact between artistic subject and actual economic exchange. Do you want to talk a little bit about your experience with planning an exhibition for this type of venue?

JMI: I think anytime you put art up, you have to consider the space. This was a great opportunity for me, to be downtown and in a wealth management office, right across the street from the Wells Fargo Headquarters. I have an augmented reality piece placed there, so I was actually very excited to have a show at Spare Change Artist Space. We did do some planning about the pieces, since many of them are videos, but I don’t feel like they were in any way altered to make them more appealing to the clients at Rhodes & Fletcher. Sean and Pamela have been great to work with too, so I haven’t felt like I needed to make compromises with the work.

AC: I know the works are not directly related, but there’s an interesting relationship between the augmented reality piece, in which businessmen are seen falling from the sky in front of the Wells Fargo Headquarters, and the flattened suit on the floor, “Pressed.” The sight of the flattened suit in the office, or on the marble floor of the lobby is reminiscent to a scene from a noir film, and can be read as the final landing place of the falling businessmen. Is it your intent to invoke a dead body with the placement of the piece?

JMI: No not necessarily. While any suit has a relationship to the body, I’m more interested in it’s symbolic nature. This was the first suit that I worked on and actually it’s the oldest piece in the show. I believe I made it two years ago, and it was originally the matrix for the prints that are in the current show, Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4. I had to remove all the excess material from it so it would fit in the press and during that process it was torn in some areas. Afterward, I felt that it was actually very compelling on it’s own. It’s the by product of something else and very much appears worn out and used. It portrays the way these ideals have been pushed to their extreme, nearly destroyed. It is very much about subversion and showing a powerful thing to be abused and powerless.

AC: Speaking of things well pressed, your video “Downtown” shows an interesting perspective on your morning ritual. Where did you learn to iron a shirt like that?

JMI: I don’t actually know. I think when I was younger my mother did show me, but since then I’ve sort of figured it out on my own. I iron my shirts almost every morning, so I’ve come up with my own technique.

That video, Downtown, actually started from another piece that was created from the parts of a business suit, 5.3L V8. In preparation for the installation of that piece, I spent hours ironing the different parts of the suit and I became very interested in the act of ironing. It’s a daily act that is important for maintaining the meaning or our clothes. It also represents our ambitions and of course, larger ideas of our economy and business.

AC: I also was thinking about your video “Downtown” in relation to the notion of myth, which you use to talk about your work a lot. I started to read the daily ironing as ritual in almost a religious sense – like you were making preparations for some larger ritual, or sacrament or performance in relation to masculinity, and the myth of professionalism. Am I reading too much into that?

JMI: “Downtown” is the most hopeful and most recent piece in the show. I do think there is a ritualistic aspect of it. Rituals are used to produce an outcome. They are acts of faith. In the same way, I see ironing is as an act of faith that we believe produces an outcome. We believe that it makes a difference in our professions and in many ways it is a very hopefully and optimistic act.

To iron is to believe that it will take you somewhere better, whether that means employment, or a promotion or a raise. It shows that you care about your appearance, but it’s also about making the object as close as possible to it’s template. The iron removes all of the wrinkles and the imperfections to bring clothing to its ideal representation.

I chose the song “Downtown” to go with it because it too is extremely optimistic about the myth of downtown. It is a place where all ills and worries are cured. I liken this to Neo-liberal ideas of the free market, as a solution to all problems, even an ethic unto itself. At the same time though, the song is very repetitive, perhaps at the point of becoming unnerving. There is an aspect of indoctrination that I’m hoping to get across from that repetition.

AC: Repetition comes up again in the video “Stress Test,” which reverses and repeats a crash test of a hummer. I remember a conversation you and I were having with Pamela Rhodes at the opening reception about the “Stress Test” piece. I had really read the hummer crash test as a beautiful metaphor for the impending doom of excessive capitalism, but you brought up all of these other points which I think really added to my understanding of the work. Can you maybe elaborate on that a bit?

JMI: The crash test piece, “Stress Test” is less about impending doom and more about the aftermath of such an event. As the video runs in slow motion we watch the car return into its pre-crash state. The crash has happened and now we are watching the pieces come back together. Viewing the projection is both about our desire for it to be put back together and our need to analyze and understand the event that occurred.

For example, after a crash we try to reconstruct why the event happened in the hopes that we prevent it in the future. The IIHS does these to analyze car safety and to rate that safety. As I am pointing out, this is not unlike the stress test that the government has put banks though. At the same time, we desire the object to become whole again, because it is a past event and this primarily has to do with the Hummers symbolic nature. The Hummer is representative of American military force and to some imperialism. Shown here in its consumerized form (not related to the military version), it represents American excess.

The idea of owning a symbol of American military prowess, that you can drive your kids to school in, with terrible gas mileage, I believe is a pre-recession American ideal. Hummer itself was put out of business during the recession, and we tried to sell it to China. Ironically, the deal fell through for what some believe had to do with the cars’ bad gas mileage.

In general though, my work has to do with the resiliency of symbols. The auto industry exists today, but in a different form but we still deem it as “American”. Instead of gas guzzling SUV’s we champion electric vehicles, because cars represent something “American” and this idea and symbol is very important to us. That is why the car is in reverse and slow motion, because it is about our desire to return, to fix the idea and yet it is also a basic illusion. Sorry that’s a long response, but there is a lot going on with the piece.

AC: I wonder if you consider your performance “The Market is up/ The Market is down,” and the subsequent video piece you show in this exhibition “Hidden Labor” a conversation about labor and class in relation to the financial world. The sheer physicality of your effort makes me think about what else and specifically who else is making the shifts actually happen.

JMI: For “Hidden Labor,” I became interested in the work that happens as a result of market volatility. The piece that is being manipulated (the cubicle from “The Market is up/ The Market is down,” was altered based on if the market that day ended up or down. If it was up, we put it together. If it was down, we took it apart. All of this was done when the gallery was closed, so that the result would be surprising. It was to demonstrate the quick and almost magical connection between small fluctuations in numbers to real physical outcomes. In “Hidden Labor,” I am highlighting the work that went into that process. I wanted to demonstrate the economy and the labor that exists from the continue fluctuations of the market.

AC: Speaking of labor, what are you working on in your studio now?

JMI: I have a few pieces in development right now. I’m working on a piece that includes three office chairs. The first one was just in the Root Division 10th Anniversary Alumni show. When I’m finished with all three, I’m hoping to find a space to have them installed vertically. I also have a couple other videos that I have been toying with, along with a piece that would include airbags. So there is always something that I’m slowing chipping away at, but I’m always trying to push into new territory. Many of the pieces in this show represent completely new mediums and ways of creating art for me, whether that was a few years ago or just a few weeks ago. It’s both exciting and uncertain, but that’s also what makes it interesting for me.

AC: Thanks for sharing this work, and for talking with me. Looking forward to seeing what’s next.

Downtown: Work by John Mark Ikeda, is currently on view through February 28th, 2013.

A closing reception and artist’s talk will take place on February 28th from 6 to 8 pm at Rhodes Fletcher LLC.

Learn more at www.rootdivision.org